Grace Nickel’s Devastatus Rememorari is deceptive. As you enter the hushed gallery space the installation invites you in through its quiet elegance. The abstracted tree shapes, arranged in a grouping that floats on its salty surface, are at first ephemeral. It is only as you come closer that you realize Nickel’s work is evoking collective ideas of devastatus rememorari, while simultaneously hitting the viewer with remnants and traces of individual memories of loss.

Devastatus Rememorari is a departure from Grace Nickel’s internationally respected work in architectural ceramic forms that reference the interplay between clay and light. This earlier body of work, described as “beautiful,” with an “element of the sinister,”1 was largely composed of lamps rich with symbolic meaning. Awarded entry in to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) in 2007 for this work, Nickel could have easily continued creating these “metaphorical lamps” that channeled her interest in the natural world. To her credit, Nickel took a leap of faith and departed from the safety of controlling elements from the natural world. The result is Devastatus Rememorari – a tribute to the awesome, random forces of nature and our human attempts to understand and control the resulting chaos.

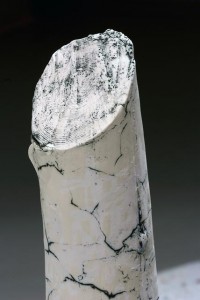

While Nickel’s earlier ceramics implied a “dynamic between control and accident, order and randomness,”2 this installation lets go of suggestions of restraint and instead pays tribute to the terrible pandemonium unleashed by natural elements. Tree forms were a natural transition for Nickel, with their powerful, elegant lines and similarity in scale to her standing lamps. Nickel has pushed herself to work taller than ever before, and the stacked clay casts made from moulds that compose these forms parallel the fragility and strength of trees. Slowly, Nickel has developed something akin to an obsession for the cultural treatment of trees.

Her studio has grown into a resource centre for the social life of trees, with black and white photographs of trees taken in Winnipeg, Halifax and China. Some of these trees are truly devastated, like the cracked and damaged trunk images she took after the Red River floods in Winnipeg, and most familiar to Haligonians, the shocking images of thousands of flattened trees in what was once the majestic forest of Point Pleasant Park. During her 2007 China residency in Xi’an, Nickel was fascinated with the care taken to wrap rope around trees to protect them against winter weather.3 Her tree photos focus on how they are presented and protected in urban cultural situations, while concurrently celebrating the resilience and growth symbolized by the tree. It is noteworthy that Nickel had difficulty finding a significant body of writing on the complex human relationship with trees: trees as memorials in and to nature; trees as reflections of human care and human neglect; trees as optimistic metaphors for growth.4 It seems we take trees for granted until we lose them. Nothing is more shocking than the sickening sound of an enormous tree being ripped by its roots during a hurricane or tornado. Nothing reminds you more of your own fragile scale in relation to the larger objects of nature.

The scale of Devastatus Rememorari lends itself to the gallery installation setting; while we are aware that these tree forms are not the largest, they are so real, so easily referenced, that we move beyond the form into a reading of the surface treatment. Not only has the subject matter of Nickel’s work undergone a radical transformation, she has dedicated the past two years to experimenting with language in her pieces, working toward the subtle conveyance of meaning from what started as a more literal relationship to text.

Whereas Nickel’s earlier ceramic art employed ornament to both entice and disturb through its flora and fauna references, Devastatus Rememorari builds upon this by adding textual elements. Her first attempts were laborious, and depended on the complex writing out of the words “Devastatus Rememorari” in slip. Worried that this approach would be dismissed as too decorative, Nickel moved on to create a variety of textual surfaces, ranging from incised carving and applied words to photo transfers. The result is surfaces on the tree forms that are built of text that has been layered, abstracted and made almost impossible to read. This process of literally working through the terms for devastation and memory is analogous to the repetitive movements that can comfort during the grieving process. Nickel’s physical movements through these words, the ideas they embody, and the ornamented abstracted surfaces that result, bring individual mourning and loss into the collective sphere.

Devastatus Rememorari has been designed to reflect the idea of devastation in relation to tree forms. Installed in a teardrop shape, all the trees in the exhibition lean along the same path as if holding on with all their might. In the aftermath of Hurricane Juan one of the most compelling sights was that of the blown down trees, all felled in the same direction. Analogies to Hurricane Juan in this exhibition are no accident. Beyond reminding the viewer of the physiological realities of mourning, the teardrop shape reflects the pattern of hurricane activity. The trees are grouped together, standing in a bed of salt that is reminiscent of tears, and the dry, parched space where nothing grows. The salt also serves as a reminder of the ocean sprays that battered Point Pleasant Park during Hurricane Juan.

Grace Nickel is an expert at ornamentation, and in Devastatus Rememorari she balances the surface statements on her tree forms with the larger collective message of the exhibition. Read from a distance the solemn grouping of trees is unified; up close, the individuality of each tree form is distinct. The subdued colour palette composed mainly of white, black, bronze and earthy greens encourages reflection and quiet memories. Bronze symbolizes something beyond the tree – a reminder of the precious objects of worship and sacred ceremonies. But bronze also operates as a metaphor for the sacred nature of trees, and their central role in helping us understand natural tragedies. It is no surprise that thousands of mourners made the pilgrimage to Point Pleasant Park after the hurricane, to gaze through their tears at the unbelievable number of magnificent trees scattered across the ground. Bronze reminds us of the memorials and tributes we pay to those who have fallen, and to the small plaques we love to place at the base of trees in our hopes that nature’s shrines will live on forever.

- Glen R. Brown, “Fire and Light: Grace Nickel’s Metaphorical Lamps,” in Ceramics Monthly (January 2007): 41. ↩

- Ibid., 42. ↩

- Grace Nickel, NSCAD University lecture, 26 February 2007. Nickel was one of ten Canadian ceramic artists chosen for the FLICAM (FuLe International Ceramic Arts Musuems) project at the Fuping Pottery Art Village in China. Their work forms the charter collection of the Canadian Ceramic Museum in Fuping. ↩

- The book that most influenced Nickel’s perception of the social life of trees was David Suzuki’s Tree: A Life Story (Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 2004). ↩